Brian Evenson:

[Untitled]

with images by John Sellekaers

Click thumbnails to view images in lightbox.

Gone

Near dawn, Dawkins shook me awake. "Jenkins," he whispered. "It’s gone!"

"Gone?" I said. "Good God, man, but that’s impossible."

"But true nonetheless," he said.

Immediately I buttoned my sidearm and holster over my nightshirt and slipped into my breeches. Dawkins, forewarned and thus forearmed, was lugging the gattler. Together we started down the hall.

"Shall we wake the others?" he asked.

"Yes," I said. "Wake Smith." But as he started for the fellow’s door, I called him back. "No, no," I said. "No point in putting anyone else at risk."

From the look on his face I determined him to be wondering if this was meant as a reproach to him for awakening me.

The door was slightly ajar. When we reached it, I pointed to it with an index finger. "This is how you found it?" I asked.

"Yes," he said.

We stared through the crack. Nothing.

Very carefully I removed my sidearm and eased the door open wide. There was no sign of the creature, the room bare and empty and pale.

We advanced, step after step, Dawkins in the lead. "I can’t understand," he said. "It can’t just have vanished into thin air."

"And yet," I said.

He turned to look at me, and froze.

"Good God, Dawkins," I said, "What is it?"

And then I heard it, a slow whispering just behind me, almost seeming to come from just within my ear. I was just starting to turn when Dawkins stopped me with a gesture. I watched him cock the triggers and slowly raise the gattler.

"Jenkins," he said in a low voice, aiming the weapon seemingly at my head, "for God’s sake, don’t move."

Out of Sight

Only after we found our plans thwarted with some regularity did we begin to be suspicious. How did they always know where we were going? And how was it they were always there before we were?

It was Sorben who first began to reconsider the scrawled words on the wall, just over and above the fence. Half-visible in a lattice-work of shadow, they were difficult to make out. "Keep" he was fairly certain the first word was, though perhaps the word continued into the shadow to end in "-sake" or "-er."

Watching him sound out what he could see of the words, trying to make sense of them, the rest of us became interested. Thorberg finally found a stepladder and climbed up to get a closer look.

But in the end the words themselves were a great deal less interesting than what we found on the other side of the fence, just out of sight, listening in.

For Now

"That’s it, then, Dawkins?" I asked, still somewhat shaken. I could still smell the gunpowder on my skin, and my ears were still ringing.

"Yes, Jenkins," he said. And then after a pause, admitted. "More or less."

"Good God, man," I said, unable to keep my voice from rising. "What do you mean ’more or less’?"

"No longer anything to fear for the immediate future," Dawkins said.

"But not dead?"

"I missed."

"How could you miss, Dawkins?" I asked. "How many rounds did you

fire?"

He hefted the gattler. "A few hundred," he admitted.

"And you missed?"

"I missed you as well," he said, somewhat defensively, "and, except for the once, your nightshirt."

I looked down, fingered the hole. I had been wearing, luckily, my second best nightshirt. "And so where is it?" I asked.

His eyes opened wide. "Why, you’re wearing it," he said.

"Don’t be a fool, man," I said. "It! Not the nightshirt: it!"

"Ah," he said. "I pursued it down the hall, gattling my way after it—"

"—still missing it," I said.

"Still missing," he conceded. "I had it cornered, but the door at the end of the hall, well…"

"You don’t mean?"

"I’m afraid I do," he said.

He gestured me out of the room, led me down the hallway to the window. There, outside, beyond the bars, I caught a brief glimpse of it, waiting.

What will Smith think? I wondered, though I could imagine perfectly well.

"At least we’re safe," said Dawkins.

I said nothing.

"For now," he couldn’t stop himself from adding.

The Expedition

On the twelfth day of our journey across the frozen tundra, just as we were setting up camp, Smith espied something through his field glasses.

"Take a look at this, Jenkins," he said to me. "Tell me what you make of it."

I took the glasses and gazed through them. There, in the middle of the whiteness of the slope, was something still white but less white, a vague interruption of the deadening regularity of the landscape.

"I don't know, sir," I said.

"I'll be dashed if I do either," said Smith. "Take one of the men and have a closer look."

I'd started off when he called me back. "Who shall it be?" he said.

"Sir?"

"Who shall you take with you?" he asked.

"I thought Clark, sir," I said.

"Clark?" he said. "Knobby Clark? No, it just won't do. Knobby's hardly expendable. Take what's his name, that other fellow, the dim one, name not unlike yours."

"Not Dawkins," I said, my heart sinking.

"Yes, that's the one," he said. "He's the fellow. Off with you."

I sighed and went to get Dawkins. We each took with us a repeater and a pair of snowshoes and set out.

As we came closer, Dawkins periodically regarded it through the field glasses.

"What do you think it looks like?" I finally asked.

"I don't know," said Dawkins. "Perhaps bones."

I commandeered the field glasses and looked. Yes, he was right, it resembled nothing so much as bone. But of what sort of creature? And how had that creature come to be wandering in wastes such as these?

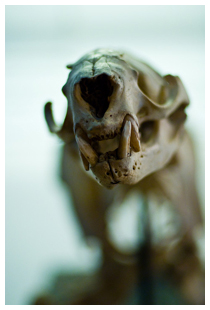

It was near dark when we finally arrived. We stopped at a little distance and stood in contemplation. It was a skeleton unlike anything either of us had ever seen before, catlike in the shape of its skull but sharply fanged as well, and with a strangely elongated neck. Inordinately large, too, the whole skeleton nearly twice the size of a man.

"Good God, man!" I said to Dawkins excitedly. "Do you have any idea what we've found?"

It was at that moment, with a low whispering sound, that the bones began to move.

All Along the Route

All along the route there had been indications we should turn back, but Pickering, driving, was not to be dissuaded. He nudged the vehicle past the outstretched limbs of trees, maneuvering down increasingly narrow streets, until the streets themselves became first gravel and then dirt, finally deteriorating into little more than animal trails.

"Shouldn’t we go back, sir?" Dawkins asked from the back seat.

"Shut up, Jenkins," said Smith.

"But I’m Jenkins, sir," I said.

"That’s immaterial," claimed Smith, twisting his head back to look at me. "Pickering knows what he’s doing." He cast a glance at the fellow. "Don’t you, Pickering?"

There was, I thought, a certain hesitation in his voice.

As for Pickering, he did not respond, just drove slowly forward. We progressed wordlessly, listening to twigs and branches scrape the sides of the vehicle, hearing the long grasses whisper against the underside of the carriage.

Eventually, the evidence became irrefutable. Ahead was a sign, a sturdy wooden barrier behind it. Pickering pulled the vehicle to a stop, just stared.

We sat there a long time, in an embarrassed silence.

"Well, Pickering," Smith finally said. "What do you have to say for yourself?"

But Pickering said nothing. Instead, after a moment of staring, he threw the vehicle back into gear.

We rumbled slowly forward, toward the sign.

"But sir!" cried Dawkins.

"Be quiet, Jenkins," said Smith. "And you, too, Dawkins. Pickering knows what he’s doing."

Even after all that followed, it took Smith some time to admit to us that he had been wrong.