Andrew Malan Milward: Kansasana

#9: THE FINAL SHOWING

The Grand Theater in Topeka was full, the crowd comprised of a mixture of well-dressed couples and solitary young men. Looking smart in his red vest with bright gold buttons, the Negro usher emptied ashtrays and swept dust from the floor boards into a small pan before the lights dimmed and he quietly returned to the lobby, where he listened to the start of the accompanying orchestral score. That fall Governor Allen had seen the film while on a trip to Los Angeles and returned to Kansas determined to address the problems of a film that in his opinion, while powerful and certainly popular, had no educational value, arousing only the memory of a time most folks would just as soon forget.

When news of the ban came, theaters filled and seats for this night’s final showing had long been haggled over, price-gouged, and bargained for. It would be four years before Birth of a Nation would run in the state again. Spurred by a Supreme Court ruling that would deem it an accurate account of the Civil War and Reconstruction and pressured by the loss of potential sales, the ban would be lifted in 1924. It would run for eleven days straight at the Grand, a first for any film, and estimates of paying viewers were as high as 20,000 across the state. But this night, when there was reason to believe they were the last Kansans who’d ever seen it, there was a shared feeling of import, of having witnessed a significant historical moment in the life of their town and state. These viewers would return home, forgiving the film for its 190 minutes, those short stretches they’d dozed off and shuttered awake at a swell in the music, and tell their neighbors and coworkers they’d never seen anything like it. Maybe the best picture ever made. The silent pleasure they’d take in the loose-jawed awe of the listener.

For his part, the usher would tell anyone who asked that night that he’d shirked his duties and snuck back to watch the film through the slim part of the red velvet curtains in the back of the theater. But, in truth, he’d been in the lobby, listening to the score’s dramatic swoop as he watched the streetlights illuminate the slow creep of automobiles on a cold February night, when his boss caught sight of him and repeated a favored phrase: If you can lean, clean. And later that night, after he’d swept the floors a final time and collected the trash beneath the seats, he bumped into a friend on his way home. They stood in the alleyway and shared a cigarette. When the friend asked if it was as bad as they say, the usher, thinking of that music he’d heard, trying to imaging what kind of picture could accompany the sound of something so grand, shook his head. Nah, ain’t even words for what its goodness is ’bout.

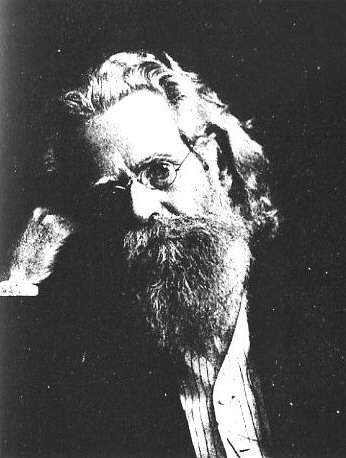

#81: ELEGY FOR A COMPLICATED MAN, PART I: MOSES HARMAN

The outrageousness of the image: you, old man Harman, 75, breaking rock in a Joliet prison with your spectacles and wildcat hair. This after fleeing Kansas and its 10 years of courthouses and penitentiaries, all because the government, under the aegis of Comstock, opened your mail and read an article you edited about a woman driven insane by the abuses of her husband, an article that equated forced sex within marriage to rape. You were obscene and for that they let you out just in time to die. And you, you smiled as you raised your pickaxe and felt the angina crush your chest.

The outrageousness of the image: you, old man Harman, 75, breaking rock in a Joliet prison with your spectacles and wildcat hair. This after fleeing Kansas and its 10 years of courthouses and penitentiaries, all because the government, under the aegis of Comstock, opened your mail and read an article you edited about a woman driven insane by the abuses of her husband, an article that equated forced sex within marriage to rape. You were obscene and for that they let you out just in time to die. And you, you smiled as you raised your pickaxe and felt the angina crush your chest.

I’m curious, Moses, what of your contradictions?

How does an ordained minister come to call for the abolition of religion? And what business did a Missourian have enlisting to fight for the Union—a Union which, by the way, did not accept your lameness, and which you’d later want abolished, because people could not truly be free in life and marriage until the barriers of the state were removed?

Educator, Anarchist, Suffragist, Abolitionist, Newspaperman, Farmer, Eugenicist.

Under these circumstances, I’ll allow myself a one-time usage of the word freethinker, but don’t get greedy Moses, because your out there was so out there it detracted from the substance of your riotchouesness. Was it necessary to change the name of your newspaper from the Kansas Liberal to Lucifer, the Light Bearer? and then to express disdain when people mistook it for a Satanic periodical? Might that have made the authorities pay more attention to what your little rag was publishing? Was it essential to configure your own calendar, starting not with the year Christ was born, but in 1601, the year in which the astronomer Giordano Bruno was executed, ushering in what you called the "Era of Man"? Might that have undercut the legitimacy of your calls for birth control?

You weren’t ahead of your time, you were willfully outside of it.

Listen to me.

My uncle is a libertarian, who once ran for the school board on the platform to abolish it. Who once tried to start a charter school, telling me with a straight face he could teach a student calculus in 25 minutes if the child hadn’t had his mind dulled to complacency by public education. Who, for a period of years after his wife died, accepted unemployment as he worked to produce propaganda attacking the Nanny State that would fill up his house to the point it was difficult to walk around. The last time I saw him he expressed true bafflement after recounting a story of how he and his friends made an Independence Day float depicting a tableau, in which he, draped in green bed sheets, and holding the torch of freedom, stood behind the bars of a makeshift jail cell guarded by his buddies who were wearing brown shirts with large, gold badges pinned to their breast reading FED. Those idiots thought we were neo-Nazis, Andy. Neo-nazis!—got us barred from the parade next year.

Were you, Moses, like my uncle, not aware, or did you just not care? Do things occur in life that callous us to our means if the end seems true enough? Like watching your wife and daughter die in childbirth. Or seeing your other daughter arrested for living with her partner before being lawfully wed. Is it too easy to say these events not only account for your views on contraception and marriage, but how you went about advocating them? I think, Moses. I think of my uncle and how, when his wife was dying of cancer and screaming in the middle of the night, he had to travel from their home in Illinois to a pharmacy in Indiana because of state regulations limiting the amount of drugs a patient could receive. I think, Moses. I think of your wildcat hair and your Trotsky beard.

78: THE FIRST MARTYR OF KANSAS

We know a little, not much. The year, for instance. 1542. Coronado, searching for the Seven Cities of Cibola, wound up in the land that over 300 years later would organize itself under the banner of Kansas. His party stayed with the Quivira Indians for 25 days, where they found hospitality, straw-thatched villages, plentiful crops, but no gold, as his guide, whom he called "the Turk," had promised. So, discouraged and bored by his futile journey, he strangled the Turk and turned around, returning to New Mexico. A year later, however, one of the Franciscans who’d been with him, Father Juan de Padilla, returned to Quivira with a Portugese guide, determined to convert the godless. I don’t know why he chose Kansas over all the places he must have traversed with Coronado. Nor do I know why they killed him. Perhaps his guide had struggled with the translation. Perhaps he didn’t understand the Quivira already had a religion that made sense of things as they were and maybe they didn’t understand what he meant when he said he wanted their souls to be okay in the afterlife. Maybe they understood each other too well.

KOTEX

Thank you for all making the trip here to Garden City on this fine March day. Though I make no claims as to qualification, I’ve been asked to preside over things and feel a few prefatory remarks are in order before we begin.

I’ll have you know that those of us gathered here in this room represent 24 counties. 24 beautiful West Kansas counties, which themselves represent countless more towns. Towns like Liberal, Ulysses, and Mater—wonderful towns that have been made to feel inferior to the likes of Topeka, Wichita, and Kansas City for too long. These corporate-ag issues dividing us from them now aren’t new. They’ve been going on since 1861 and for the last 131 years those of us in the west have been kicked in the mouth, year after year. Well, gentlemen, let me tell you, no more. No longer! What we want is respect and we want that respect reflected in reapportionment, school budgets, and taxation. And if Topeka won’t give us that respect, it’s time we look elsewhere. For just as these issues aren’t new, neither is talk of breaking away. Secession is no longer an idle threat to be laughed about by the politicians and media in the east. Surely tomorrow there will be articles and editorials in the Kansas City Star and Lawrence Journal World ridiculing us, calling us cranks and mad fools. You can bet on it. What’s new, am I right? But I’m here to tell you it’s no madder than any other dream that’s lead to betterment, whether it was defying Pharaoh or the King of England. It is a dream that can be made real if we fight for it.

Close your eyes and picture it, will you. Can you see it? Envision a new state in the new millennium, founded on respect, fairness, and equality. Maybe we split this state right in half, or maybe we join with another. Maybe it’s us and eastern Colorado. Or maybe we look south and this new state will join Kansas with parts of Oklahoma, and Texas. That’s what we’re here to discuss, debate, and dream.

Now I think that it’s about time I shut my mouth already. Let’s get on with it, shall we.

Chair recognizes the gentleman from Grant County.

#31: TOWN ERASURE, 1955

How quickly it came, here and gone in a few minutes, and still powerful enough to stop time at 10:35 pm. 77 people, not a building left standing. We were finding limbs for weeks.

By the time the hail arrived, the tornado watch had been lifted over an hour earlier and most had gone to bed thinking we’d avoided the worst of a not un-frequent summer storm. My beloved liked working the late shift at the switchboard, listening in on lovers’ calls and the midnight gossip of bored housewives. Always, in the morning over coffee, keeping me abreast of the "real news" in town. When that hail came, I called the telephone exchange. She was busy, saying only that the news stations in Wichita weren’t reporting any alarm, that I shouldn’t tie up her lines any longer.

What were those last calls she patched through? What had she heard that kept her on the line a minute too long, preventing a scramble to the basement?

Sometimes after the person I’ve been speaking to hangs up, I stay on the line, and in those static-dead moments before it switches to dial tone, I say her name, my beloved, and I’m able to conjure a vision in which she has left the exchange in time, or maybe she’d been sick and never gone in at all, and there we were in the cellar, the two of us huddling below the storm’s swirling, electric belly until it’s 10:42 and dead quiet and we’re rising from underground, poking up our heads to survey what remains.

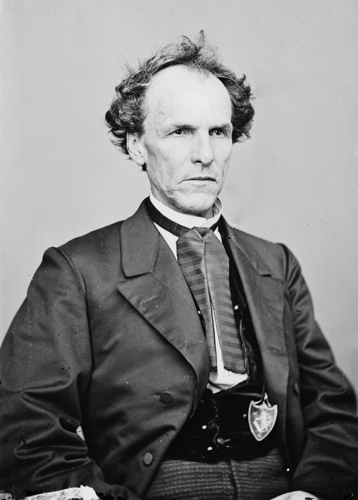

#11: ELEGY FOR A COMPLICATED MAN, PART 2: JAMES LANE

The severity of your thin, angular face. An arch seriousness undercut by neither a receding hairline nor the daffy wisps sprouting from the sides of your head. The hard stare and easy grimace that makes understandable the capacity for both violence and civility, war and governance. Your multitudes contained you, eventually sending you to the sanitarium.

The severity of your thin, angular face. An arch seriousness undercut by neither a receding hairline nor the daffy wisps sprouting from the sides of your head. The hard stare and easy grimace that makes understandable the capacity for both violence and civility, war and governance. Your multitudes contained you, eventually sending you to the sanitarium.

Lawyer Lane. Lincoln Lane. Free-State Lane. Senator Lane. Kansan Lane. Partisan Lane. Jayhawker Lane. Brigadier General Lane. Jim Lane. Union Lane. James Henry Lane.

Requiring a special hearing and congressional vote, you became the only man to simultaneously hold the rank of general and senator. And when you were leading the red-legged jayhawkers of the Kansas Brigade on raids against Missouri guerillas you understood there were things politics alone would never accomplish. Like the Sacking of Osceola, in which you were responsible for the deaths of nine people, as well as the looting of the town. Afterwards, your men were so drunk they could barely march, barely able to lead those hundreds of newly freed slaves back to Kansas, and you, for your part, hitched up a special cart to carry a piano and a dozen silk dresses you thought your wife might fancy. And you understood, too, and accepted the consequences of your necessary transgressions. Like how two years later when Quantrill lead 400 Missouri bushwhackers on a raid of Lawrence—you knew you’d be at the top of his death list. With all the guns in town locked in the armory, every man and boy in your town was left for slaughter, and over 185 were, but you, you escaped. Initially too proud to flee, you tried to defend your family’s honor with a single, dull,ceremonial saber awarded for military service, before fleeing out the backdoor of your mansion and into the tall stalks of a cornfield. You ran for a mile in your pajamas until you reached the house of a farmer who gave you an ill-fitting pair of trousers and a tired, old plough horse. And with the few men you could rouse in surrounding towns, you raised an impromptu militia, and this motley crew even got close to Quantrill’s men before they made it to the border and disappeared. So you had to take your revenge politically with the Lincoln-backed General Order #11, which forced the remoal of all residents from four Missouri counties, who Union Brass suspected of aiding the guerillas. Regardless of their loyalties, these families had their towns pillaged, their homes burned to the ground.

It’s no surprise that after the Civil War ended, some three years later, your sanity slowly began to depart and you sought rest at an asylum in Leavenworth. With the last bit of reason you could muster, you announced wishes to have a biographer do justice to your life, for posterity. But when John Speer, a newspaper editor from Lawrence, arrived in Leavenworth the only thing you could tell him was, The pitcher is broken at the fountain, over and over again. So Speer left, telling the doctors he’d return again in a week, when the senator was feeling better. But that second visit never happened, for as you were riding in a carriage, accompanied by two orderlies, you pulled a revolver from your coat and fired it into your brain. And still you didn’t die. No, forgetting would not come that easy.You had to lie in bed three more days before the memories allowed you to leave. During this time, when visitors came to see you, the only thing you could do was take their hands and raise them to your bandaged head, and, nearly in tears, say, Bed, bad. Bad, bad.

ANDREW MALAN MILWARD’s stories have appeared in places such as Zoetrope, The Southern Review, Conjunctions, Comumbia, and Best New American Voices 2010. He is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and a former James C. McCreight Fiction Fellow at the University of Wisconsin. He lives in San Francisco, where is is a John Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose University.

ANDREW MALAN MILWARD’s stories have appeared in places such as Zoetrope, The Southern Review, Conjunctions, Comumbia, and Best New American Voices 2010. He is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and a former James C. McCreight Fiction Fellow at the University of Wisconsin. He lives in San Francisco, where is is a John Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose University.