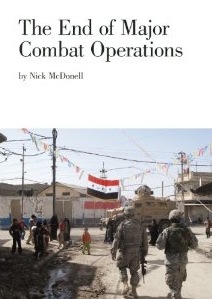

Nick McDonnell: The End of Major Combat Operations

In early August, nearly eight years into the U.S. occupation of Iraq, Barack Obama delivered a speech promising to withdrawal all U.S. troops from active combat duty. For those of you keeping track at home, this is the second time this war that American combat operations have officially ceased—the first being George W. Bush’s "Mission Accomplished" speech in May of 2003, that universally embarrassing publicity stunt in which he landed on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln in a flight suit to declare that "major combat operations in Iraq have ended" a mere six weeks after they had begun. Nick McDonnell’s appropriation of this phrase for the title of his latest book is, of course, ironic: combat operations had certainly not ended THEN, and they are still not over NOW. Even Obama’s optimism came with an alarming caveat: "The hard truth is, we have not seen the end of American sacrifice in Iraq."

So for American service-people on the ground, the official U.S. policy change will not magically solve the problems they encounter in the line of duty, which frequently involve a paradoxical mixture of destruction on one hand and nation-rebuilding on the other. McDonnell’s book provides readers a compelling window into just such situations. In a series of unflinching and unforgettable series of dispatches from Baghdad and Mosul, he portrays a post-invasion Iraq where nothing is as simple as it seems: every household is entitled by law to own one AK-47 assault rifle, which can blur lines between insurgents and innocent civilians; U.S. troops are well-protected from all-too-common IEDs and grenades when inside their armored trucks, but they are but they are routinely assigned to patrol streets so labyrinthine that they must travel on foot; an infantryman’s training readies him to kill and destroy, but McDonnell trails a group that must strive to do the opposite on a "chai-op"—a sort of indirect counterinsurgency mission, named for the tea that soldiers drink while sitting in diplomatic meetings with local Iraqi community leaders. Diplomacy and rebuilding are higher causes, to be sure, but not causes that these men necessarily have the resources or training to accomplish.

In all of these cases, the vividness and honesty that McDonnell brings to these stories ensures that readers see his cast as individuals, characterized with depth and humanity, whether they are Iraqi children pestering troops for candy handouts, Colonels and NCO’s on base, or civilian men and women peering into the streets from the windows of a thousand-year old mosque in the heart of the war theatre.

Readers meet Gu, "an extremely light-skinned Brazilian" and a twenty-two year old sergeant in the 1st Cavalry Division. McDonnell clearly likes Gu, but struggles to understand him: "not because he looked like a white boy, called the black guys in his platoon nigga, had a south Boston accent, and sang in Portuguese under his breath. I couldn’t figure him out because he was a decent guy who, if he didn’t take pleasure in killing, didn’t seem to mind it that much."

Then there’s Nabeel, an interpreter hired by US contractors, so loyal to the American cause that he didn’t even bother to conceal his identity while he commuted to work, as most "terps" do. For this, he got a death threat slipped in through the window at night. "So Nabeel took his Kalashnikov and his pistol and his wife and children right then… hailed a taxi at gunpoint and drove to a relative’s house." A translator risking his life for the American cause is just one more paradox of the war—there are other Iraqis who would just as gladly kill to stop it.

As McDonnell tells these stories, he does an excellent job balancing his critical eye with true respect for the individuals he represents. He clearly supports the troops as people, while remaining objective and often condemnatory, when necessary, of the larger political policies and realities of the conflict. McDonnell’s work is political, but not partisan. Rather, the anti-war overtones of the text come rather from his natural progression as a journalist—he is primarily a witness, but the sights he sees are so confounding and barbaric that he can’t help but meditate on the senselessness of it all.

Stylistically, McDonnell follows closely in the tradition of Michael Herr’s seminal Vietnam War correspondence, Dispatches, alternating between moments of lyric description, cerebral reflection, and the gritty, down-to-earth viewpoint of man with his boots kicking foreign soil. This style works to captivate readers’ attention, even in a scene as simple as a brief encounter with a security contractor: "His influence concentrates down into the tool in his hands, the gun that was waiting for him as he drove to the airport, pushing past the streetlamps, orbs of light floating in the dust, through an all-day twilight as alien to his Southern-boy roots as the first muezzin’s call, like copper though the air, that woke him up that morning in a hotel room that looked like hotel rooms all over the world."

At a slim 163 pages, "The End of Major Combat Operations," may not achieve the depth and breadth of Herr’s landmark work of journalism, and history will probably not to canonize it in the same way, but today’s readers should consider McDonnell’s work with an even greater gravity, if for no other reason than its overwhelming contemporary relevance. Besides, to wax intellectual in comparisons of the two conflicts would be to miss McDonnell’s point entirely: for all the talk of withdrawal and de-escalation and leaving the Iraqis to clean up their own internal civil battles, the conflict in Iraq is of no one else’s making—America is still at War, with all of the horrifying realities that entails.

Nick McDonnell

Nick McDonnell