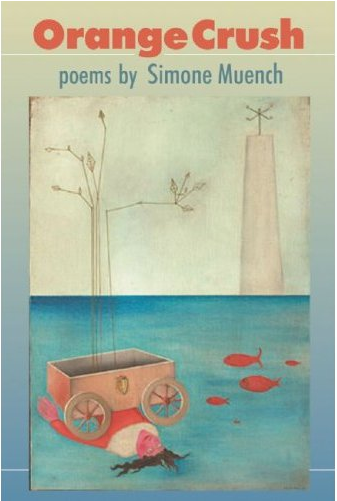

Simone Muench: Orange Crush

Simone Muench’s Orange Crush opens with a poem called "Hex," the opening lines of which set the tone for the rest of the book: "Trouble came and trouble / brought greasy, ungenerous things." "Trouble" is a he, and throughout these pages we see girls, women, and the Trouble they’ve known. The poems in this collection, Muench’s third book, privilege sound, but never at the expense of losing the reader with associative jumps too far to follow.

The book is divided into Record, Rehearsal, Recast, and Redress. Record, as one might expect, provides a sort of women’s history to the book. "Hex" and "Psalm" raise the association between women and witchcraft while poems like "A Captivating Corset" and "You Were Long Days and I was Tiger-Lined" evoke an enjoyably smutty Victorian flair. Yet these poems are admirably restrained, and in the case of "A Captivating Corset," formally adept; the rhymes, at first true and relatively straightforward ("damage" and "slippage") lace the poem together like the corset of the title. As the poem progresses, the rhymes become more and more slant ("dispersed" and "bird"), giving the impression of a loosening but in no way unraveling structure.

The meat of the book is in Rehearsal and Recast, where Muench writes about "Orange Girls," a term describing seventeenth century girls selling oranges (and more) outside of theaters. In Rehearsal’s "Orange Girl Suite," a multi-part poem, these girls are part commerce, part ephemeral beauty, with "pear dust on our skin / sarsparilla sounding our / fizzied song in sailor mouths." That beauty is increasingly under violence, however, as killers enter the poem, and the orange girls become bodies to dispose of, as in section four where "a man folds the girl up in newspapers / her wet hair a string of taffy, a rope, something" and in seven, where another is "dragged along the waterfront, / dropped in a dumpster wearing / a yellow shawl and pearl earrings." The orange girls themselves, so often portrayed as dead or dying, seem ciphers, and when Muench insists "she is glass, she is straw / she is waiting for us / to wake up through her eyes" – it’s hard to do so. The effect is not unlike that of a horror movie, where we watch with fascination and repulsion as our cast of characters is killed off one by one.

This litany of girls’ deaths starts to seem a bit repetitious, and, even more troubling, passive. The antidote to this is Recast, in which we get the "Orange Girl Cast," another multi-part poem wherein Orange Girls are "played" by several of the author’s friends. These Orange Girls are blasoned by Muench’s descriptions but never reduced to objects, full of movement and agency, and even danger, as seen in the lines:

" … Sweet Kristy of the corset, born of Anne Boleyn and a bird collector, born of alum and blindfolds, born to unzip men’s breath, their clamorous wrists with an alphabet on her breast, a switchblade pinned to her taffeta thigh."

While conflating a woman’s power with her sexuality has its own problems, it’s a relief to see these Orange Girls fleshed out and zinging off the page. The poems in this book are unrelenting in their examination of women and violence, the female body and its commodification, and Muench, bravely, realistically, doesn’t offer us an easy answer of sisterhood or empowerment to combat these disturbing images, but asks us to look, look, and look again.

Simone Muench

Simone Muench