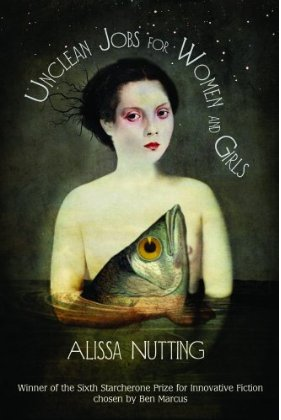

Alissa Nutting: Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls

One of the blurbs for Alissa Nutting’s debut collection, Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls, describes her voice as "the futuristic love child of Mary Shelley and the Brothers Grimm." Add George Saunders to that threesome—hell, why not make it an orgy?—and you’ll have a sense of the sheer imaginativeness of Nutting’s stories.

Her settings are places of dark wonder, worlds where humans are forced to host at least one other organism in their bodies, where people are slow-cooked in kettles, where porn is shot on the moon, and where Hell is fathered by a timid and sensitive Devil. It’s no coincidence that many of these worlds are the stuff of our worst nightmares. They’re each an exaggeration of a specific modern malaise, yet the raw emotionality in these pages transcends satire.

Nutting’s narrators—all female, all first person—use alcohol, drugs, sexuality, denial, and animals (yes, animals) to defend themselves against the ills of their worlds and against their own marginalization. They protest their vulnerability in voices almost shrill, until they crack. And these moments, when Nutting’s characters open up and expose themselves as women with all too human wants and sorrows, are what make her stories so memorable.

Each story is a job description of a sort, though not the kind HR departments volunteer. From "Knife Thrower" to "Ice Melter," from "Teenager" to "Cat Owner," Nutting hones in on the way jobs and gender roles define women, and on the absurdity of those definitions. Professionally unsatisfied, Nutting’s women and girls seek love in the most familiar and most unlikely places. Take, for instance, the lovely final lines of "Corpse Smoker": "So we kiss, and the weird smells of the morgue suddenly turn into something tame and slippery, something our lungs can slide over like jelly, something that can hold our hearts steady through our own quiet death-rattle." These stories are all death-rattles in a sense, quiet protestations against a fast-approaching demise; records that we haven’t always been what we’ve become.

All of this (especially the death-rattle stuff) seems to suggest that Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls is a relentlessly dark and serious book, but that’s not the case. Humor runs rampant in these pages. It’s what keeps them from becoming too Grimm. Nutting may allow her narrators self-pity, but they’re never allowed to be unfunny. Her prose resists pretension. Her similes and metaphors are always quirky, often deviant; they take a delicious minute to unfold and transport the reader.

For all the pleasure to be found in Nutting’s inventiveness, in some instances the stories’ premises eclipsed the characters themselves. While Nutting closes each story with lines that make a reader’s heart go all big and leaky, there wasn’t always (especially in her short shorts) an emotional spine supporting the surface eccentricity. In moments, the fantastical veered from inspired to random, and the prose read a bit like being told a spouse’s dream pre-coffee (Thor is in Hell, but he keeps eating people’s brains, so he’s turned into a rhesus monkey without a brain, but then the Devil relents and gives him a mini-brain and puts him in charge of the new rollercoaster in Hell). This is a minor quibble—all in all Alissa Nutting’s dreams are a pretty awesome place to find yourself.

Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls was chosen by Ben Marcus for the Starcherone Prize for Innovative Fiction. Alissa Nutting has also published work in Tin House, Fence, BOMB, the fairy tale anthology My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me, as well as many other journals. She received her MFA from the University of Alabama, where she was editor of Black Warrior Review. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and an editor at both Witness and Fairy Tale Review.

Alissa Nutting

Alissa Nutting