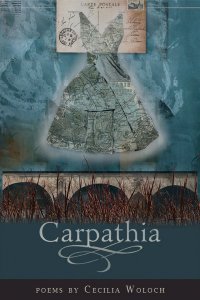

Cecilia Woloch: Carpathia

Cecilia Woloch’s collection Carpathia is about distance, both physical and emotional. Her poems occupy a lush landscape where the natural world succumbs to loss, where "fat bees [fall] into the wine" and the ghost swans have "wings of death." The highlights of this collection are her numerous postcard poems which feel balanced in their attempts to be both strange and authentic without becoming burdened with ironic oddity that I’ve seen so much in recent poetry. Her postcards move, making leaps with each new sentence, and their prose-poem form opens these poems up to be more peculiar in a way that’s all-together successful. Here’s an exempt from the ending of my favorite, "Postcard to I. Kaminsky from a Dream at the Edge of the Sea":

Hurry, I thought, and my hands were like birds. They could hold nothing. A feathery breeze. Then a white tree blossomed over the bed, all white blossoms, a painted tree. "Oh," I said, or my love said to me. We want to be human, always, again, so we knelt like children at prayer while our lost mothers hushed us. A halo of bees. I was dreaming as hard as I could dream. It was fast—how the apples fattened and fell. The country that rose up to meet me was steep as a mirror; the gold hook gleamed.

As the book moves, there’s a notable shift in tone as attention is given to loss: to deceased, to bygone lovers. But even then, Woloch far from indulges in despair. In her poem, "Why I Believed, as a Child, That People Had Sex in Bathrooms," she discusses a child’s perspective of death and sex with humor and grace, a feat that any poet knows is not easy. The poem begins:

Because they loved one another, I guessed.

Because they had seven kids and there wasn’t

a door in that house that was ever locked—

except for the bathroom door, that door

with the devil’s face, two horns like flame

flaring up in the grain of the wood.

By the poem’s close, the subject matter has drifted to loss, a theme that hangs in some degree over each of the poem’s in this collection. It ends:

… I didn’t know

he would ever die, this god in a body, strong as god,

or that she would one day hang her head

over the bathroom sink to weep. I was a child,

only one of their children. Love was clean.

Babies came from singing. The devil was wood

and had no eyes.

Occasionally the poems in Carpathia drift toward the sentimental, a line difficult not to cross with such subject matter. Poems like "My Old True Friend" and "Seven Years After Your Death," as their titles suggest, veer off into a nearly maudlin space that perhaps is more closed-off than her other poems. But even during these rare moments in Carpathia, Woloch’s language is always lovely. She is a luminous poet, and while her work often is not surprising or complicated, I hardly mind that many of these poems lack punch. The poems themselves are written with such attention to music and emotive instinct that each poem earns its place in this collection due to the texture of Woloch’s language, which is always beautiful. Lines such as "Wherever I am, wherever I walk, my feet touch the earth and my heart says bone" ("Ground") kept me sighing and reading onward. This book is full of such lines. I’ll end this review with "Anniversary" in its entirety, which is one such poem that resonates with its clarity, its straightforward language, and honest spirit:

Didn’t I stand there once,

white-knuckled, gripping the just-lit taper,

swearing I’d never go back?

And hadn’t you kissed the rain from my mouth?

And weren’t we gentle and awed and afraid,

knowing we’d stepped from the room of desire

into the further room of love?

And wasn’t it sacred, the sweetness

we licked from each other’s hands?

And were we not lovely, then, were we not

as lovely as thunder, and damp grass, and flame?

Cecilia Woloch

Cecilia Woloch