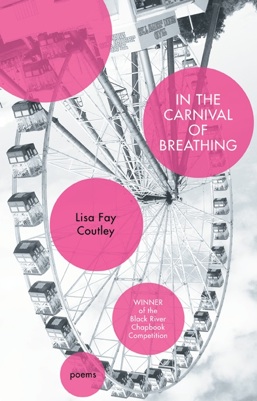

Lisa Fay Coutley: In the Carnival of Breathing

In a post on The Poetry Foundation's Harriet the Blog, Joel Brouwer describes the current state of poetry as conceptually driven, focused more on thematic arcs between works than the accumulation of a miscellany of poems. "Poets more and more these days," he argues, "conceive of writing projects and then write poems to fulfill those projects." A survey of loglines from some recent thematic collections might include "poems concerning the author's interest in the D-Day landings" for Overlord by Jorie Graham, "poems in the voice of Daniel Boone" for A Companion for Owls by Maurice Manning, or "poems filtered through the lens of film noir" for Black Maria by Kevin Young.

Brouwer vacillates between condemning and praising this trend. In one respect, such hooks can help a young writer distinguish herself from her competition. As Brouwer writes, "Since so many first books get published through the medium of contests these days, young poets feel pressure to stand out from the crowd, and one way to do that is to have a hook." The flipside to such a trend is that poets will feel pressured to expend their "18 poems in various forms about your mom" into full-length collections since the book is "the coin of the realm in the poetry world." The problem? Even reading about the best mothers might become tiresome after 20 pages.

Lisa Fay Coutley's chapbook In the Carnival of Breathing could provide a strong argument in favor of the "book with a hook." Although it spans only 25 pages (and thus escapes the danger of developing 10 pages of Bolivian tin mine poems into 48, to use Brouwer's example), Coutley illustrates the metaphoric possibilities and emotional power of a collection that organizes itself around a central metaphor. Not as overt as some of the examples Brouwer lists, Coutley's logline could read "poems about one's relationship to water."

More specifically, many poems in this collection, Coutley's second chapbook, center on the tension over access to water and the conflict borne of the speaker's departure from a lake basin to a landlocked desert. "I went west from water to learn drier states, / climb steeper grades and test those runaway / truck routes," she writes in "Woman from Water," and many of the poems find the speaker struggling to negotiate this new environment. In "The Study of Lakes," the speaker of the poem muses on a world devoid of water:

No one blessed the faucets or prayed

for hailstones to halve like human eyes,

so the baptism by thistle went unnoticed. It was easier

that way—to say no one was watching.

The Nalgene bottles went fast & the flasks even

faster, but by night we rediscovered energy …

The world Coutley creates is dangerous and frequently on fire—flames sprouting in a submarine, buildings burning, a subway ablaze. A poem takes the title "After the Fire." Another name-checks Zippo lighters. It is a world where water (when present) can serve as the foil for the flames, as a place of refuge, as in "My Lake" where water forms a cradle, and as a fountain of longing.

In "Much Later, From Space," which appropriates many of its lines from a textbook on aquatic ecology and limnology, an oxbow is transformed into two lovers spooning, representing the speaker's need for intimacy. In "To Sleep," water becomes a desire for deep rest. This sense of longing drifts through the entire collection, threads on lost lovers commingled with reflections on the struggle of single parenting.

In a collection so drenched in loss, Coutley tempers depression and pain with subtle humor and tongue-in-cheek sarcasm. Sure, the speaker of "My Lake" has been hurt, but she also "owns boxing gloves," blinds men with her beauty, and "doesn't take any shit." When her sons pantomime shooting her, the speaker of "On Home" imagines "the going rate // for hormones, then picture[s] an eager group / of eBay bidders" and earlier, references the "that's what she said" joke. Elsewhere, a defiant speaker claims she is "sick of men who will fall in love / with me" ("Yakima, 2019"). Another speaker "trot[s] cleanly away" from a relationship with an inconsistent man.

This bravado might begin to grow tiresome and insincere if the poems didn't nearly always cycle back to the speaker's vulnerabilities. (It also helps that readers don't fully believe the self-proclaimed toughness). One speaker might threaten to leave her kids, but instead, she finds reasons to stay. Another admits to being "too tired for climbing" the first morning after experiencing a loss. In "After the Fire," the speaker sings to comfort her son even though she doesn't "believe in magic." It is a classic move in literature—to expose the weakness of a seemingly invincible character and thus win our sympathy—and in Coutley's hands, it is utterly devastating.

Aside from the emotional power of this collection, Coutley wins by being an impressive, well-honed practitioner of lyric verse. Nearly all of her poems crackle with assonance and internal rhyme, and she's a crack shot at crafting lines you wish you had written. Whether it's her unexpected imagery ("My lake / learned early to rest the needle without a scratch"), her enviable skill at making profanity sonically beautiful ("his boots resoled & restitched. But fuck it"), or her control of the line ("And so it begins, with a slap on the ass"), there's much to admire in this collection.

Readers might initially be drawn in by the drama of her poems, but it's the craft in In the Carnival of Breathing that will reward readers as they read and revisit this collection.

Lisa Fay Coutley

Lisa Fay Coutley