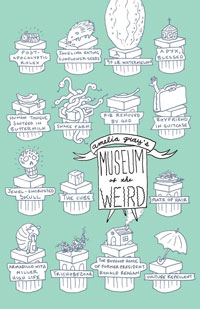

Amelia Gray: Museum of the Weird

Roger, a medical sanitation worker, is invited over to his neighbor Olive’s place for dinner. The last time he was there, she served human tongue, which she’d ordered from a monastery, sautéed in buttermilk, and served with wasabi and chili sauce. This time, he enters her apartment to find her lying on the floor with a bleeding and bandaged foot. “I decided I might try and eat my toes,” she tells him. “But now that I’ve started, I don’t think I should move.” This is the premise of “Waste,” one of the stories in Amelia Gray’s collection of flash fiction Museum of the Weird. The characters and situations in this book are as-advertised: animals go out for drinks, giant cubes appear in the middle of picnics, and waiters serve plates of auburn hair between the soup course and entree. We meet people who are riddled with neuroses, paranoia and obsessions of all kinds. Autosarcophagy is a reoccurring theme: characters eat or attempt to eat their own hair, arms, and toes. They also eat paper, tree leaves, computer screws, and love—which comes in the form of “sticky tangled masses” of goop and which one woman claims is poison.

These stories are very funny. Gray is particularly adept at the sort of humor that ambushes you when you least expect it. Although most characters are unfazed by the surreal and fantastic, there are moments when one of them will become aware of the oddness of what’s happening and the result is disarmingly funny—like an actor breaking the fourth wall.

In “Waste,” after Roger finds Olive bleeding and toeless, he kneels beside her and uses her belt to make a tourniquet.

He unbuckled her silver belt and reached with it under her dress. He looped the belt around the top of her leg and tightened it. His hands were not shaking.

“Sit on that lose end,” he said, pushing it under her. “I hope that works.”

“You brought flowers,” she said, blinking.

“Olive,” he said. “You cut off your toes.”

There are a number of moments like this, in which a character seems to snap out of a dream and see the absurdity of his life. In “The Darkness,” a penguin and an armadillo sit at a bar (no, this isn’t the start of a bad joke), drinking gin and Miller High Life, respectively. Between bits of small talk, the penguin Ray tells his date, Betsy, about how he fought “the darkness,” which he describes as “evil incarnate.” At the end of the story, he sits back in his bar stool and says, “I’m just a penguin in a bar, drinking my gin out of a fucking highball glass for some reason… Doesn’t make any goddamn sense.” We never learn what the darkness is, but his attempt to peck his drink out of the sleek highball glass calls to mind a war veteran’s displacement in a world that’s come to seem emasculating and full of indignities.

The collection is not merely a freak show. As bizarre as these stories get, the characters are deeply human (animals included) and the worlds that they inhabit are creepily familiar. In “Vultures,” a young couple concocts ways to capitalize off the fears of citizens in a town besieged by vultures. “We play off people’s security,” the boyfriend says. “Take a guy afraid they’ll find him while he’s playing golf. Sell him a golf umbrella with metallic panels.” At times the vultures seem like a metaphor for terrorism, at other times harbingers of death, at still other times a phenomenon completely unique to the story. Because these pieces incorporate elements of fables, it’s tempting to read them as allegories. Fortunately, they are never that simple. In “Fish,” Dale, a fisherman, is married to a paring knife; his friend Howard has wed a bag of frozen tilapia. In some regards, the story alludes to same-sex relationships—Dale and his knife are asked to leave the church, and the fishermen’s friendship is somewhat homoerotic. But the story is equally concerned with the men’s attitudes toward their “wives,” and their belief that women are, quite literally, objects. “Obviously,” Howard admits, “a bag of frozen tilapia was different in many ways from a woman, though in many ways it was the same.” The story resists easy interpretation and ends with a moment that is completely unexpected.

There are twenty-four pieces total, and not every one is brilliant. A few of them are so strange they become disorienting. There’s also a tendency toward humor geared at nothing other than entertainment, as in “Code of Operations: Snake Farm,” which is exactly what it sounds like (“The hours of operation will be determined daily via MAJORITY VOTE by the snakes”). But it’s difficult to criticize such cracks when the writing is genuinely amusing and oftentimes what appears to be a mere gag has, on second read, subtle depth. For the most part, these stories are glimpses into worlds that are enchanting, disturbing, and a lot like our own. The best succeed in exposing that which has become too familiar—real-world relics that need to be displaced, dusted off, and displayed in fresh light so we can see them for the oddities they are.

Amelia Gray

Amelia Gray