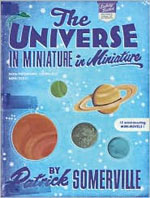

Patrick Somerville: The Universe in Miniature in Miniature

In "The Machine of Understanding People," the closing novella of Patrick Somerville's story collection, The Universe in Miniature in Miniature, Tom, a failed lawyer and recently-divorced drunk, gets a telegram notifying him that he's been left an inheritance from a billionaire uncle he didn't know he had. The gift is not what he expected: what he gets is a contraption straight out of a Jules Verne novel—an antique diver's helmet that allows the wearer to enter the consciousness of other people. At first, the machine seems to work wonders. Tom realizes that "it drew you in. It freed you. It opened you up, knowing people. It stabilized you." But just when the story seems to be heading toward a Hallmark ending, Tom accidentally enters the consciousness of a man stabbing a boy to death. "Seeing the kid get stabbed was too much," the narrator says of Tom's decision to abandon the machine. "There are some experiences he doesn't want to understand."

This fatal stabbing is at the center of the book, an event which we see in different stories from a variety of perspectives: the boy's mother, the cop arriving at the scene, the ER doctor who fails to revive the child. The Universe in Miniature in Miniature is not a novel in stories, but the pieces are linked in more subtle ways. The stories are like planets orbiting the same sun, each offering a new vantage point. The machine appears in other stories as well—including the title piece, in which it's the subject of an art student's project. The collection's title takes its name from one of these hypothetical projects: a model of a father and son putting together a model of the universe.

If there is a thematic strain tying these pieces together, it's the redemption—and the difficulty—of connecting with another person. In the title story, three students set up surveillance cameras in the home of a dying teen named Ryan Conrad. The narrator, Rosie, and her friend Lucy watch the footage each night and find themselves wondering, "What does Ryan Conrad dream about? What can be inside of him?" Rosie concludes that there's no possible way for them to know, adding, "But I have guessed." In "Easy Love," a young doctor recalls his brief relationship with an Iraqi family that owned a liquor store near his old apartment. At one point, the narrator considers the seemingly inconsequential transactions he has with people every day:

There are all different degrees and qualities of transactions with anonymous vendors; you can be blocked from the start or you can immediately be pulled in to someone else's kindness, someone else's world, by a look. Not unlike love. A comment about the weather can be a bridge. If I want anything in my life, I want bridges.

Blending standard realism and Saunders-esque surrealism, Somerville's prose is no-nonsense and sparse—there's very little landscape or descriptive detail. Unsurprisingly, the author is at his best when he's plumbing the depths of his characters' minds. This skill is most apparent when given the space to gain momentum, as in "The Machine of Understanding Other People," which runs a full seventy pages and includes several longer scenes. Unfortunately, several stories are diced up by section breaks that make for truncated scenes, many of which end abruptly and without punch. Some of these vignettes, though, succeed as microscopic glimpses of big, universal truths. In a way, the stories comment on themselves. They profess an unabashed optimism about art's capacity to bridge the distance between self and other; more often than not, they succeed in doing just that.

Patrick Somerville

Patrick Somerville