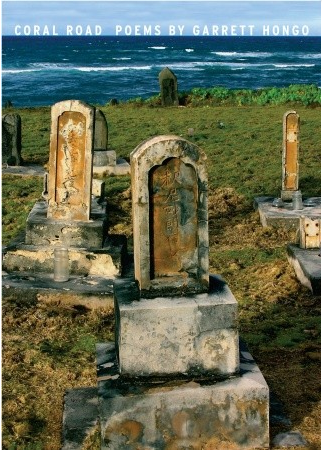

Garrett Hongo: Coral Road

Garrett Hongo, a Japanese-American born and raised in Hawai'i and California, has turned the geographical and cultural landscape of his past and present into nearly thirty years of poetry (and prose – a memoir, Volcano, was published in 1995). Yellow Light (1982) and the Lamont Poetry Selection River of Heaven (1987), his first two collections of poetry, move seamlessly in landscape from Hawai'i to Los Angeles, Japan to the American Pacific Northwest, from urban to rural, from peace-time to war. Through documentary-style description, loping and sonorous rhythms, and Whitmanic line-lengths, these two collections address issues of racial and ethnic injustice, displacement, loss and coming-of-age. Coral Road, his most recent volume, continues in this same vein as it moves the reader from cane plantations, where Japanese people were forced to work during the 1930s, to a detention camp in Arizona, to a World War II soldier in Italy, to Hongo's current home of Oregon. No matter the landscape, in this new collection Hongo wrestles with his present and how it relates to his past and the past of others.

Split into five named sections, Coral Road is organized by historical voices and situations. The first section, also named Coral Road, follows a speaker who is looking back on the Hawai'i of 1919-1920, when twenty Japanese laborers fled their work on cane plantations, fueling a strike. This focus on history and recollection marks much of the book, as sadness, helplessness, and cultural displacement inflect nearly all of these poems. This theme of displacement is emphasized by the use of both Hawaiian and Japanese language, as well as the occasional use of broken English (the frontispiece, "An Oral History of Blind Boy Liliko'i," is the best example). A real highlight in this section, "Pupukea Shell," follows a speaker, presumably Hongo himself, who recalls a Shell gas station (off of Kamehameha Highway in Hawai'i) from his childhood, and its many associations, both familial and otherwise.

When I see it these days, boarded up and rusting,

The window glass of the office spiderwebbed with cracks,

The pumps gone like pulled teeth and the timbers and underside of the awning

Blackened with mildew and spotted with blooms of a brown, fungal scourge,

I remember that a pair of lovers met there once – a shopgirl and a dark local boy

With long, black surfer's hair reddened by the sun.

[Hongo p. 16]

The final two lines of this excerpt show Hongo at his strongest – simple, clear, and narratively driven. This more objective approach helps make concrete the varying landscapes through which the reader travels.

Aptly named, the second section, "The Wartime Letters of Hideo Kubota," consists of epistolary poems whose speaker, a Japanese-American named Kubota, is detained in Leupp, Arizona during WWII. The recipients of each letter are poets, ranging from Pablo Neruda and Miguel Hernández to Charles Olson and Polish poet Tadeusz Różewicz. "Kubota Returns to the Middle of Life," addressed to the aforementioned Różewicz, effectively intersperses phrases from Różewicz's "In the Middle of Life."

This is a man this is a tree this is bread,

You have taught me. People nourish themselves in order to live.

And I ate what was given for the sake of returning to the midst of life,

So I could talk to the water, so I could stroke the waves in the lagoon with my hand,

So I could converse with the river running through our village

Past cane fields down to the fishponds and out over the reef.

The epistolary form allows each poem sentimental "wiggle room," and Hongo takes full advantage in this section; each epistolary demonstrates camaraderie and empathy for others who have known oppression and discrimination.

The speaker in the third section, "The Art of Fresco," a Japanese-American in Italy, continues the collection's vision of "elsewhere," when home becomes that "elsewhere." Through a series of linked persona poems in the third section, Hongo continues description through ekphrasis, which comes to fruition through the speaker's discovery of Italy's art scene. Its use is particularly prominent in the poem "Preliminary Studies":

I made a sketchbook of studies as soon as I was home:

Jiichan driving his mule across the village garden patch,

Ploughing up the earth, row of shacks visible in the background,

A poi dog scratching itself in the dirt street, while a flock of kids

Chased after a cane truck, one stooping to pick up a dropped stalk,

And, over them all, a waft of soot from the mill stack

Spreading like a long, slim banner of black gauze across the page.

In this third section, Hongo's consonance and long-line rhythms help structure each poem. At one to two pages each and with largely end-stopped lines, Hongo's approach to form privileges content, whether that content is narrative or descriptive in nature. This privileging of content emphasizes the historical voices at hand, and the research which accompanies much of this collection as a whole (as section introductions and an extensive notes section attest).

When Coral Road is less successful, its heavy use of description simply delays the narrative thrust of a given poem, as opposed to complementing it. The landscapes which Hongo describe captivate the reader, but given the book's considerable length (94 pages), it is inevitable that certain images will repeat (ocean, sky, coral, for example). This repetition alone is not the problem, but rather that the description often does the same work in each poem: to set the scene. As vivid as they may be, the landscapes can eventually become static for the reader, even amid Hongo's use of lyricism. The opening poem of the fourth section, Kawela Studies, demonstrates this use of "scene-setting":

Drizzle of rain pattering on the dwarf palms, dark towers and blue parapets of clouds

Over the ruffled blue gingham of the sea, sweet scent of seawrack and fresh life

Borne on the wind

That ambles along the sands and sticks of drift like a nosing poi dog

Wigwagging from the lava rock point along this thin scythe of a beach …

Immediately after these two stanzas, the poem makes a more declarative and striking opening: "I'm home again…" The poem becomes a survey of Hongo's literary life, the push and pull from his past to his present, his identity, as a writer, and otherwise. These issues make up the heart of this particular poem, and there are others as well, where a more stripped down approach might better serve the narratives at hand.

However, there is much to admire in Coral Road. Hongo's skill is clear, and equally is his commitment to voices, narratives and landscapes not often approached in American poetry, and for that he should be praised.

Garrett Hongo

Garrett Hongo