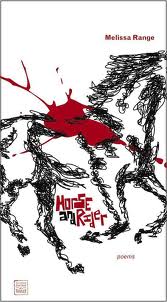

Melissa Range: Horse and Rider

For as long as I’ve studied poetry, the general consensus from teachers and fellow students has been the same: contemporary poetry shouldn’t rhyme. Or if they do, they should use only slant rhymes, sneaky rhymes. And if they must use hard rhymes, then never—never—write rhyming couplets. Maybe it’s because rhymed poems are singsongy, sonically predictable. Maybe it’s because parents and aunts everywhere believe only good poetry rhymes. Blame Whitman, or the modernists, or whoever you’d like, but after centuries of rhymed poetry, the poetry we read, write, and admire in the twenty-first century by and large does not rhyme, which is one reason why Melissa Range’s debut Horse and Rider is both striking and important.

Not all of Range’s poems use traditional rhyme schemes, not even a quarter of them do, but enough rhyme to merit the discussion. As Robert Fink states in his introduction, Range’s poetry “is an old thing made new,” and it’s precisely for the reasons a book like Horse and Rider shouldn’t work that it works so beautifully. “They throb in graveyards, haybales, cohosh, clover / with the vengeance of this land, which is never over” (“New Heavens, New Earth”) writes Range, who follows a sonic logic that moves her poems to surprising, wild places. It’s that tension which drives Horse and Rider.Using a sonic structure allows Range to constantly push against borders, and as a result of risking predictability, her poems are always unpredictable, a paradox only a few poets could pull off. Intelligent, charged, full of fervor, Range makes of her “voice a staff turned snake/ turned brass turned tambourine” (“Horse and Rider”).

The book, divided into three sections, confronts notions of war and violence, the cruelty one person can inflict on another. “That the body is merciless in its pining,” she writes in “September Trees,” “requires no banner.” The second section is a chorus of armory—eleven weapons and one workhorse who are each given a poem through which to speak. It is in this section that Range takes her biggest risk. The poems are presented to us as a series of riddles, full of kennings and hard rhymes, paying stylistic homage to the riddles in the Exeter book. These poems are the collection’s most playful, and their formal departure from the rest of the book reminds me in part of Terrance Hayes’s series of “A Gram of &s” from Hip Logic. “Bonnie boy, I’ll get beneath your bodice” promises the arrow. “Fidgety Fletch, flighty flibbertigibbet” answers the bow. These poems nearly become overly precious at points, but by the time we get to the section’s final poem, “The Rope,” one of the strongest in this collection, this series has culminated poignantly and powerfully, earning its place. “I have held / the breath of women, too, and children” says the rope, unwillingly tied into a noose. “Twine was made for more than this.”

The first and third sections are subtle mirrors of one another: the book begins and ends with a poem featuring birds, and the poem “September Trees” from first section is in conversation with the penultimate poem “October Trees.” They differ, however, in their attitude toward violence. While the poems in the final section offer a sense of hope, of the world healing itself through nature, the first despairs: “I too wear the scars of Tennessee / like the flat-topped mountains where trees once grew. / Like you, I’d kill to keep it, and like you, I do” (“Dragging Canoe”). But it’s the book’s final gesture that resounds the most for me: “Unchapel us,” Range writes in “At St. Dunstan’s-in-the-East,” “from the works of gold and glory. / And may the green flame in our flesh take up the story.” The notion of nature as a counterforce to man’s violence is beautifully explored in “Force,” a poem dedicated to Oscar Romero:

To the far-sighted priest stammering every name

of the disappeared—¡presente!—like it’s his own,

because it is: because I was taken, aflame,

inside the stem to a place where atoms moan

in whirling congregations, where the tree’s coarse

green hem is for the healing of the nations.

Range makes a case for tradition in Horse and Rider, and after reading it, I’m convinced. She is a timeless poet whose grand, truth-telling, word magic is haunting, and whose book deserves more attention than it’s received.

Melissa Range

Melissa Range