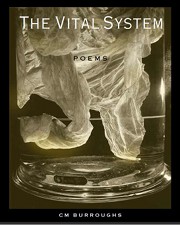

CM Burroughs: The Vital System

The voice in CM Burroughs’s first published collection of poems, The Vital System, pleads like a hole in the heart: “Sister, speak/ to me after this I’m sorry/ I dreamt it like this.” In a poem titled “Clitoris,” the speaker “likes it rough. Likes it/ Dug. Says done right, I am fragments/ Of Heaven.” In the face of violence, the speaker “could not breathe. As a bird groping a wire.” The speaker leaps like a stop-motion deer in a field: “He meant creek, you know. But I got [the usage] and [the origin] wept. He was my student. Sweet and smelled like a delicious word. Anyway, the question wasn’t so much What as When.”

The speaker in The Vital System calls out from somewhere between hemispheres, which means that reading these poems is the business of both body and mind. Burroughs binds together confession and performance with a twine of decapitating, gorgeous lyric: “I must tell you, and possibly you know, there is only this stage.” The language here is molten and dreamlike, chewy, even; it begs to be read aloud. And Burroughs’s use of sound and typography makes for a book that nearly buzzes and beeps. Her form is often anatomical, and the verse here is punctuated, bracketed, footnoted, numbered, and struck out.

There was a gash where he said “[

!]”

Where Burroughs stands out is that such experiments are not trivial, or clever for the sake of it. These poems are concerned with, and make craft from, the tensions of that which is unbearable: “So much has happened. I’m black. I have a dead sister.” Crucially, these poems are not the utterances of a body in isolation; the speaker persists in a social world, singing, “Pain, that magenta snail,/ Take it, she says, take it away.” Go to the fault line where a body meets its environment, and listen there for an unflinching song about violence, desire, loss, and hope; what you hear is the The Vital System.

Burroughs’s poems beseech and swagger, narrate and adore; most of all, they sing about being: “I, in strutting cock stance,” begins the title poem, “anatomy blazing, phonic, self-/made mid-light.” Just as much, these are poems about not being: “Dying happens just as your waking happens, but backward.” The poet’s treatment of themes such as the vulnerability of the human body and the celebration of the self echo Whitman: “You are so beautiful I say it, You are so beautiful. Body.”

A standout poem is “&Glory,” which, in three columns side by side down the page, recalls when “My hair, the beautiful/ rat pile, the/ glistening tail begins/ tearing away in my hands.” Going bald—“it’s/ awful”—says this moving soliloquy of a poem, and it echoes despite its density on the page: “I have never/ been so ugly as/ I am right now. I am mourning/ right now.” Grief, filtered through the body. Everything, filtered through the body; everything called “names that acknowledge pain but don’t let it out.”

Burroughs’s poems may sing the body electric, but they do so with an updated consciousness of changing gendered and racial landscapes. If The Vital System is a party, then “testicles lay in the streets/ like confetti post-parade.” But it is not a party,

This is a treatise on loyalty. My beloved

feature of the Black man is his edge, the

tender shape of Otherness, careful valley of

chain. When he fucks me, isn’t he uprising?

(“Black Memorabilia”)

This is the same speaker who, just pages earlier, swears, “Not once was I tender.” But there is plenty of tenderness to be found in these pages, despite it all. The Vital System is one of the most interesting, relevant, and well-crafted first books of the past year.

CM Burroughs

CM Burroughs