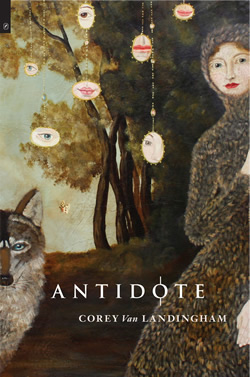

Corey Van Landingham: Antidote

Corey Van Landingham’s reckless abandon, her breathless, wild, and exhilarating voice is on full display in her debut collection Antidote, winner of the 2013 OSU Press/The Journal Wheeler Prize for Poetry. With her fresh take on surrealism, Van Landingham doesn’t shoulder her way into the crowded field of contemporary poetry; she megaphones above the murmur of the less exciting and less alive.

Consider the stacked spondees and alliteration in the book’s first “Valediction Lessons”: “The star-pit is a far-flung lamentation reflected back by the sea“ (5). Or take these lines from later in the same poem: “And tears are not liquefied brain / but maybe they could preserve a creature or / be made into a nice necklace.” These lines ape the speech of scientific textbooks to argue that grief can function as a shield, ending with the shift into the muted humor of the “nice necklace” punch line. It’s not an easy collection, possibly because, as Van Landingham argues, “it is desirable / to be puzzlesque” (“ Orchard,” 27). But it rewards deep reading with lines that are alive with sound and image and a few hard-won lessons on how to live through grief.

At her best, she seamlessly wraps together technical jargon with personal narrative as in the first “Valediction Lessons”: “Bromeliads hold their water close for later. / And have I ever been held close for later?” (5). She references the Miranda Rights when describing a domestic argument: “Anything I say can and will be used against me / in the middle of the night” (“Elegy in Which I Refuse to Turn Away,” 7). And the entire collection is filled with appropriated lines from religious texts.

Thematically, the book could be tagged as an elegy, specifically, an elegy for a deceased father. And it’s true that the presence (or, I should say, absence) of a father looms large in many of the poems. The father, and the inability to bury him, recurs throughout the collection, a repetition that calls to mind a book-length “One Art,” with the poet trying and failing to forget, an arc that culminates in an acceptance of the loss (or at least a letting go) in “Eclogue”: “When the snow melts / you will be trackless and waning” (61).

However, this descriptor is reductive, ignoring the other threads coursing through the collection. Such a tag threatens to dismiss the complexity in the collection and downplay the other elements that make Van Landingham’s writing so inventive, exciting, and pleasurable. This is not a dry lament fluffed with tired old sentiment but a collection hungry for understanding and acceptance both of loss and of coming-of-age. It demands answers on how to exist in the world and receives some advice: Van Landingham offers three “lessons” in valediction and a number of commands. In “This World Is Only Going to Break Your Heart,” the speaker is told to “love a piece of earth,” “to be simple,” and to “only love / what you can bear to break in half” (18).

The litany in “Antidote” expresses the speaker’s desire to heal and protect herself from pain, yet the speaker recognizes the impossibility of this. She admits that she “never found / an antidote against the inclination to fall asleep / while you recited your favorite songs into // my mouth” (10). In “What Will Be Untold,” a stranger is alarmed when “the graveyard you were hiding in your / chest opened up for him and he was amused” (17). The speaker of “Elegy on Sea Legs” cannot burn her father but stands “with an empty book // of matches, two hands” (25). In “Diurnal,” the speaker attempts to cast off another self: “I am done with you. I have said that” (40). However, the two selves are inevitably drawn back together: “we have the same / birthmark on our nipples, same un-photogenic / mouths” (41). Ultimately, in the end, the speaker finds that it is foolish to “avoid the splinter that will still / work its way into your heel” (“What You Erase Knits Back Together,” 60).

Although the collection is assembled from so many ostensibly disparate parts and might initially appear untamed, under the surface, it is very intelligently constructed. The repetition of titles—“To Have & To Hold“ and ”Valediction Lessons“— is the most obvious and explicit design, but Van Landingham couples this with a repetition in form (mainly with anaphora) and in image, reintroducing characters whenever the threads start to fray. One example of Van Landingham’s control concerns the connection between “Spill” and “What You Will Encounter.” The latter opens with these lines:

Something is always spilling—

bird-shape, bird-shape—

from the sky we’ve created.

The idea of spilling is one clear connection, but it’s the stacked stresses of “bird-shape, bird-shape,” mimicking the lines “Bird slick mud mask half-life” from “Spill,” that tether these two pieces together so seamlessly. The first “To Have & To Hold” and “Orchard” share a similar parallel in their lines “Easy” and “Easy enough,” both of which fall early in their respective poems, serving to counterpoint lengthy opening lines.

Other poems recall and recast images. Some of Van Landingham’s favorites images involve the moon, birds (and talons), a whole zoo full of animals, fur, throats, and ghosts. Mouths are another preferred image, as a primary means of connection (a lover singing into his woman’s mouth, a woman marking one man as hers with her mouth) but also of danger and abuse (“I have a mouth // for you to fill with mud,” “Spill,” 11).

In one particularly striking example of Van Landingham’s repetition of image, a bloated dead deer that sinks in a river is echoed a few poems later in the line, “You may feel the drowned / animal that is always coming back to you” (“Bestiary,” 50). That line in turn recalls another from earlier in the collection: “There are ghosts that swim // through me and I cannot drown them” (“The Louse,” 12). Van Landingham’s wildness turns out not to be wildness at all but a carefully controlled and well-built skeleton that supports the various shifts and turns in her work. After all, as she writes, “wildness is a process / that has to be learned” (“Eclogue,” 61).

Occasionally, images do miss the mark, giving the impression that they were generated through a free associative process inorganic to the poems in which they’re placed. For instance, in “What Will Be Untold,” she writes, “All the words to your favorite songs were / clenched in the teeth of the garbage disposal” (17). That line uses a killer verb but leaves readers puzzling out the meaning behind the personification. Mostly, though, her lines consistently stun with their specificity and uniqueness, as in this one (taken from an endless list of great lines I recorded in my notes): “Once I woke to a forest with the red light of morning pouring into my body, backlighting every bone through the thick skin of my palm” (“To Have & To Hold,” 43). Or they bring out a chuckle: “He was asking questions like What Kind / Of Beasts Are We and What Name Do You Want / In My Acknowledgements Page” (“What Will Be Untold,” 17).

Aside from image, repetition in syntactical structure, anaphora, and sound is the main trope in many of these pieces. The poems in the “To Have & To Hold” sequence are broken into sections. “Tabernacle for an Adolescence” outlines a litany of images from the speaker’s teenage years in simple sentences that all roughly fall at the same length. And many of the poems employ anaphora to varying degrees with the most drastic use coming in the book’s title poem. This repetition underscores the urgency of the collection and voices the frustrations of the speaker, and the lists of images accrete to form a cohesive world as detailed as one in a Wes Anderson film.

Recently, in naming the “50 essential books of poetry that pretty much everyone should read,” a contributor to Flavorwire placed Corey Van Landingham’s debut collection Antidote in the same company as Dickinson, Frost, Ginsberg, Plath, Whitman, and even Shel Silverstein. Weaker collections might wilt when held up to such giants, but Van Landingham has the chops to fight for her place if not among these greats, than at least alongside any other, younger contemporary writer. She’s a writer to be read, and Antidote is the gauntlet thrown down.

Corey Van Landingham

Corey Van Landingham