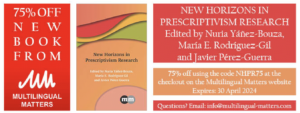

Lynn Zhang and I have a paper in the soon-to-appear volume New Horizons in Prescriptivism Research.

The book is now available on advance orders (alas, not to customers in the US yet), at a whopping 75% discount.

Prescriptivism is not a popular topic in linguistics. Many linguists think that it’s a waste of time to engage with anyone who sets out to regulate language use in pursuit of some kind of idealized ‘standard’ (think: don’t split your infinitives and don’t dangle your participles). However, if we don’t engage with those approaches, we lose a lot of potentially important information on how people use language and to which extent they are influenced by what they think is ‘right.’

Our contribution to this volume is informed by our experience as teachers of syntax classes and introductionsn to linguistics. While the distinction between descriptive and prescriptive approaches to grammar itself is crucial to the introduction of linguistics as a discipline, surprisingly little effort goes into illustrating prescriptive rules with updated examples. We often see the same examples of prescriptivism mentioned in introductory textbooks, including the proscription of split infinitives (typically with a nod to Star Trek’s to boldly go), preposition stranding, and flat adverbs, as illustrations of an approach to language that students may have encountered but that is not relevant to the scientific study of language. However, in our own undergraduate classes we have observed that many students have never heard of these rules or are not aware that many people take them very seriously and therefore are not really prepared to discuss the influence that prescriptive rules may or may not have on modern language use. The reason that these students do not consider a split infinitive ‘bad grammar’ is not necessarily that they know better than to stigmatize the use of a construction on the account of some prescriptive rule (i.e. some kind of metalinguistic awareness), but rather that they have never been instructed to avoid such constructions or are simply not very familiar with syntactic terminology (like infinitive) in the first place. It is hard to have a discussion about prescriptivism and its potential impact on language use and the harm it can cause if the data used to illustrate the approach does not resonate with the audience it is directed at. In our contribution, we present preliminary results from an ongoing study that sets out to better understand [yay, split infinitive!] which prescriptive rules speakers of Modern American English from different age groups and with different professional backgrounds are aware of [yay, preposition stranding!] and how they respond to those rules. Do younger speakers still take them seriously? Do they make a difference between using a construction in spoken or written registers? Are there constructions that elicit stronger responses than others? Emphasis is put [whoops, a passive!] on responses from people who, as students of linguistics, editors, teachers, and writers, may have higher levels of metalinguistic awareness and/or may find themselves in the function of linguistic gatekeepers for others. The ultimate goal is to arrive at a better understanding of how to approach the topic of linguistic prescriptivism in the classroom.