Interview with Meg Day

Q: You describe yourself as a “poet, activist, and arts educator.” Where do these roles intersect in your work and life? Do they ever demand incompatible things of you, or is it a peaceful coexistence?

This is actually something I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking and talking about lately because, for the first time, I’m in a position—professionally, geographically, and personally—where the three don’t always feel compatible. Or maybe they’re compatible in new and (often) uncomfortable ways? When I first encountered poetry, it was through this strange bundle of hip-hop, spoken word, country music, and ASL storytelling, each of which has a particular political edge and definitely carries a variety of class implications. I came up listening to Tupac and Biggie Smalls on the radio, but was involved in 4H and spent a few of those crucial developmental years desperately wanting to be a country music sensation. At the same time, I was encountering Alix Olson’s spoken word and finding that, as a byproduct of participating in ASL poetry nights, I had little trouble getting on stage and performing poems that felt bold in their pursuits of social critique.

…poetry is at once the most ludicrous endeavor and also the only thing that makes any goddamn sense.

I stopped teaching spoken word and participating in slams when I left Oakland in 2011, but I think there’s plenty of room to argue for the (often missing) performative aspects and role of the stage in “page poetry” readings. In the slow transition from stage to page, I frequently felt as if I were straddling some awful barbed-wire boundary that separated academia from, for lack of a better term, poetry for the people: when I was teaching in San Diego or teaching at Mills, everything was experimental and page-based and if there were performative aspects, it was called cross-genre or multi-media, whereas when I was teaching with Youth Speaks or the libraries or with WritersCorps, there was a much heavier emphasis on performance and audience and the sacred nature of call and response between poet and listener. I mean, I’m not saying anything new here—and I’m especially not saying anything new as a white kid with an excessive amount of privilege, academic and otherwise, that lets me move between communities of writers with little to no resistance. But in those moments, the triad of poet, activist, and arts educator were inseparable.

More recently, things are different for me. I don’t mean to say that teaching or writing poetry isn’t always political; it absolutely is. And I don’t mean to say that I’m not all of those things at any given time—certainly I am and feel that I am—but I find it much more difficult to participate in the trio in ways that each individual community finds satisfying. Am I making sense? When you decide to pursue academia, sometimes you make certain choices that are at once ostracizing and inviting; when you start to get older, sometimes you make certain choices that shift the topography of your daily life. I’ve gotten a lot of pushback from the queer community, for example, in the last few years—especially since moving from a coast to Utah in 2011—because I’m not nearly as visible as I once was as an activist or as a poet. Sure, Salt Lake doesn’t have the biggest literary community and you’re not going to see me on a mic twice a week, every week, but I don’t think that’s the complaint. I haven’t toured since 2010, I don’t compete in slams, I occasionally teach poetry written by dead white dudes. I’ve been called a sellout more times than I can count for leaving a place like the Bay to pursue a PhD. I’ve been called a sellout for being queer but expressing interest in starting a family. Shrug. It’s been a big shift, moving my life from a more public space to a healthier, slower, more private one.

I live in Utah now, I teach here. Here, teaching is wild activism as it is, but teaching poetry is a different kind of beautiful and insane undertaking altogether. I think a lot of creative writing instructors and professors understand that intro level poetry can be a hard sell—but in a place where young white men are shipped off on LDS missions, voluntarily or otherwise, and young white women are shamed for being unmarried and still in school at twenty-one, and young black men are surrounded by their fellow students who sit in my office hours asking how they should act around folks of color (“because I’d never met a black person before college”) or venture a guess that Martin Luther King Jr. was killed by polio, and I, a white kid carrying masculine-of-center privilege, have to watch mothers cover their children’s eyes when I pass them in the cereal aisle at a [Joseph] Smith’s supermarket, poetry is at once the most ludicrous endeavor and also the only thing that makes any goddamn sense. There are beautiful things about this salty city and I don’t mean to sell it as short as I know so many folks on coasts would like me to, but sometimes being here—and then teaching here—is so much more of a priority for me than getting on a mic or standing in a picket. I guess all of that is to say that when folks come at me about not performing as much and disappearing into “the building,” or about “giving in” to homonormativity by wanting kids, all I can think is that I have human beings in my classroom who only know how to talk to one another because of how Emily Dickinson or Bhanu Kapil or Jill McDonough or Truong Tran or June Jordan is allowing it.

Q: You recently won an NEA Fellowship in Poetry. In the current climate, governmental support for the arts feels tenuous at best or downright threatened. I’m curious whether that has made you think or feel differently about your writing, to have it receive such a nod of governmental support. What could or should the role of government be in supporting artists? Is it a good time to be an American artist?

I don’t think I did anything particularly right or wrong, but I feel the pressure to sure as hell get it right, now.

These aren’t easy questions to answer when you’re on the receiving end of such a generous, albeit governmental, award. It’s not easy to be critical and feel good about it, is what I mean. When I got the call about the NEA it was the morning of November 6, Election Day. The irony wasn’t lost on me. Would these be the last NEAs awarded if Romney were elected? What does it mean to live down the street from Romney Plaza in Salt Lake City, Utah, and receive an NEA in poetry on Election Day and teach CA Conrad’s poem, “Dear Mr. President” to a night class of conservative undergraduates while the ballots are being counted? Does it matter at all?

It’s never a good time to be an American artist. Am I allowed to say that? Probably not. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to make a living as a poet outside of academia (or in, given the odds, the state of tenure, the ridiculous adjunct pay), regardless of who’s in office, and I don’t think I could ever really encourage someone to be an artist or a poet so much as I encourage appreciation of and investment in the arts and want to participate in supporting younger poets once that option seems to them altogether unavoidable. And that doesn’t even touch on the professionalization of art that MFAs and creative PhDs participate in, or the commodification of art as it gains value only via its worth in dollars, or how $25,000 is a huge and riotously generous award but totally impossible to live off of in most places in the country, etc. Still, I don’t personally have to deal with all that much overt censorship from my government; indifference frequently affords me, especially as a white kid, the space to experiment and play with language in ways that are all but praiseworthy when it comes to this country. I’m probably not going to be killed by the government for what I write, I’m not going to be disappeared or exiled. To criticize a lack of governmental support for the arts is a huge privilege in itself and I don’t mean to belittle the space my privilege affords me to do so. I also don’t want to disregard the great amount of change that artists in American have participated in cultivating. What was it that Tony Kushner said, tongue-in-cheek, about writing Angels in America with his NEA? That he wanted to make sure the American public was on the receiving end of every single dollar’s worth?

I don’t know what role the government should have in supporting artists because I fear what kind of censorship and regulation follows. There’s a certain kind of relief in having the arts underfunded in that way, I guess, which feels shitty to say given what a fresh lens it’s given to my own experience of working and writing. I do think about my work differently, if only because there seems to be an additional window looking into my office, so to speak. People want to talk to you about the NEA, they want to shake your hand, they want to know what you did right, they want to know how you’re gonna use it best. I don’t think I did anything particularly right or wrong, but I feel the pressure to sure as hell get it right, now. At the same time, I love that there are so many people that have no idea what the NEA is. I don’t think I felt that way about it before receiving a fellowship, but I love that there are people—mainly my students—who don’t look at me or my work any differently and who aren’t afraid to challenge the purpose of poetry again and again, no matter how much money is involved.

Q: Where and with what do you write?

A part of me wishes I had a more romantic answer for you, but I’ve found that writing on a typewriter or in a notebook under a tree really just encourages shitty poems from me. I like to write by myself and I like to think about poems for a long time. In my program, the workshops are frequently structured so as to force poets to produce a poem a week: an assignment poem every other week, a poet’s choice poem in each calendar gap that’s left. Within that structure, I usually start thinking about a poem three weeks out. I carry a small moleskine and take notes sometimes, but even that is something—while religious in my dedication to it in undergrad and in my MFA—I’ve abandoned since living in a place with less traffic, less noise. I mostly just think a lot, truthfully. When it comes to writing, I like to do it on my laptop. I like to edit as I go. I used to get really frustrated that my lines would look a particular way on a notebook page and then, because of my handwriting or the limitations of the margin, they’d look awful when I’d transcribe them into a word processor. So I’ve trained myself to skip that step and simply use the machine. I’ve started thinking in different typefaces, which I think working in the letterpress during my MFA encouraged. I feel okay about it. Not great, but okay.

Q: Your poems often invokes a particular geography, or the movement of a body across place—“dreams of China Beach”; “every story/ Kansas corn could hold.” Salt Lake City is home for you right now, but you hail from San Diego and spent some time in the San Francisco Bay area. Has the geography of Utah found its way into your writing, or do you find yourself writing about other geographies now that you are in Salt Lake? What kinds of community have you found or made in Salt Lake?

I look at the Wasatch Mountain Range every day driving to campus and still can’t get over the sublime feeling of simultaneous awe and claustrophobia at being landlocked for the first time, ever.

When I moved to Salt Lake (affectionately called The Great Salt Lick), the only thing I was looking forward to, aside from the program, was the pace. SLC is just barely a city by coastal standards and while, like every other urban metropolis, it has its own slew of issues (racial profiling and the nasty lake-effect inversion for starts), it took very little time for the geography of the place to infiltrate my writing. Prior to living here, I didn’t think about urban themes in my work as geography; in the Lick, I look at the Wasatch Mountain Range every day driving to campus and still can’t get over the sublime feeling of simultaneous awe and claustrophobia at being landlocked for the first time, ever. The high desert is a strange place to live when you’re used to moving about the world at sea level, and while it took me nearly a year to learn the grid system and find good friends, the geography started showing up in my work almost immediately. I think because it’s an embodied experience it comes more easily than in other places I’ve lived and written as a transplant. So often, I think, it’s hard to find ownership over a place. Truong Tran used to say in workshops at Mills that if you are gonna write poems about Oakland—a place with fierce geographical loyalty and a rich turf history not easily lent to newcomers—then don’t spend all your lines secretly wondering if it’s okay to write about Oakland. Salt Lake isn’t like that. Maybe it’s because of the homogeneity or the religious influence, but I think it has much more to do with the fact that when you’re not from here, you wake up with nose bleeds every morning from the dry air and you gag on the dryness of your own throat while jogging in Liberty Park and you watch, incredulous, as the city wastes thousands and thousands of dollars trying to keep Temple lawns alive. It’s also not exactly a place a lot of folks end up, unless you’re born here, make a pilgrimage here, or are some kind of mountain-related sports fiend (Utah’s license plates say the state has the best snow on earth, but it’s still just cold and white to me), which I think allows for a different kind of inhabiting when you know you’ll be here (because of the program) for a series of years. I don’t know, I’ve come to love it in a way that’s mildly disturbing. It’s made me think about living differently.

Q: In your poem “Sit On the Floor with Me,” you write, “At five, I knew my name only as a chestbeat-thumped M, as three letters scratched in crayon, / knew my momma’s call / from down the aisle at church—the quick flick of wrists.” One thing I love so much about your writing is the attention to sound and different ways of hearing, not only on the level of craft (though certainly that) but also as a theme. This fixation on sound is evident in your projects past and present, from your homophonic translations of Rilke, to your experience teaching spoken word to youth, to your current manuscript, which explores the intersections of queer, Deaf and hearing languages, and bodies. Would you tell me more about your relationship to sound?

My relationship to sound is a little like my relationship to geography and place. I don’t think about it nearly as much as I used to, but I see its effects surfacing constantly. I’ve started reading aloud as I type, which has made a huge difference for me in learning to read my poems in ways that are embodied instead of merely presented. Even as I write this answer to your question, I’m reading aloud and it feels so much easier to me than trying to write quietly. I’m not done being embarrassed about working like this—I’m grateful to have a door to shut so I can do so in private.

A few months ago I sat on a panel about the intersections of Deafness and trans* identity. It was a mostly academic panel that invited members of the hearing and Deaf communities as well as the straight and LGBT*Q communities to a larger conversation about difference and marginalization in regards to sharing one’s story. I feel less invested in talking about myself these days and that seems to disappoint folks who are really invested in me telling my experience of ASL poetics and Deaf spoken word and CODAs as a hard-of-hearing bilingual (gender)queer kid. I’d much rather talk about sound. I’d much rather have a conversation about why young Deaf folks are being oralized as hearing college students fulfill their “foreign language” requirement with American Sign Language. I’d much rather engage on the topic of spoken word as having its roots, yes, in hip hop, but also in political evangelism and pulpit-pounding and advertising. I want to talk about my critical focus, which involves developing Implant Poetics and thus a space for folks who are linguistically invested or fluent in ASL to participate in the creation of bilingual and therefore bimodal poems and literary criticism without further oppressing the Deaf community.

Q: What are you working on now?

This is always a funny question to me because, for whatever reason, I adopted a sort of secrecy about my work early on in my writing career. I know this isn’t unusual, but I also rarely encounter someone who isn’t willing to talk about their work when prompted, despite their discomfort. I’m not somebody who likes to talk about the poem that I’m working on or read drafts aloud outside of workshop. I’m not somebody who thinks all that rigidly anymore about “projects” or “books” per se. I guess I can say that right now I’m writing a lot of poems about the intersections of the body with grief and the body with intimacy, and how both grief and intimacy are tied to gender. I’ve stopped writing so much about sound and instead find that I’m using sound in new ways that are not theme-related or within the semantic meaning of a piece. I feel excited about the way my work has changed in the last six months or so, as I’ve settled into a new kind of living here in the Lick. I’m happy, which is new. I know it’s ridiculous to admit, but I didn’t think I would write good poems as a happy person, but it turns out they’re better than I could’ve expected—not altogether unlike everything else.

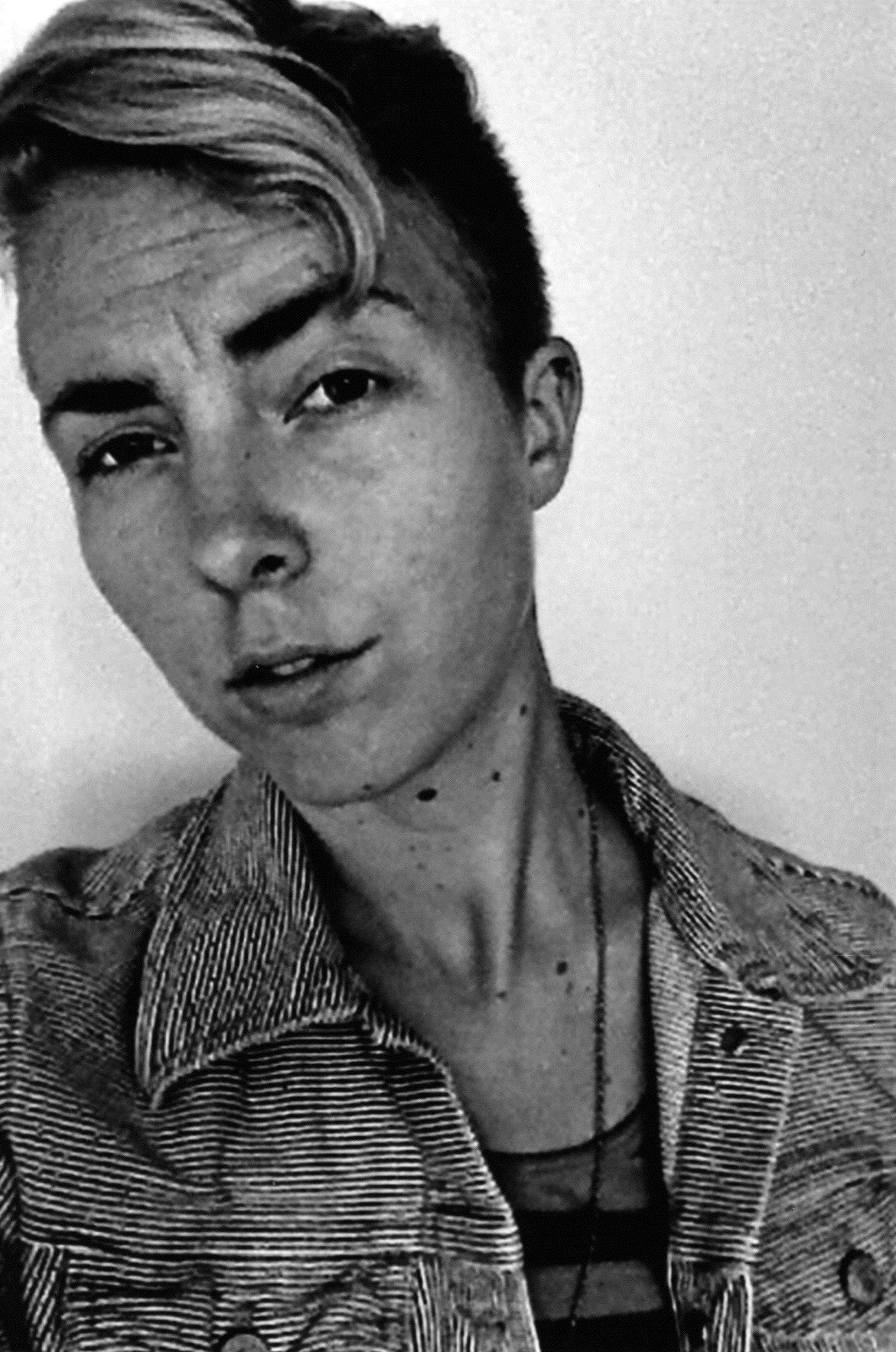

MEG DAY is a 2013 recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Poetry, three-time Pushcart-nominated poet, nationally awarded spoken word artist, and veteran arts educator who is currently a PhD fellow in poetry and disability poetics at the University of Utah. Meg hails from Oakland, where she taught young poets to hold their own at the mic with YouthSpeaks and as a WritersCorps Teaching Artist in San Francisco. A 2010 Lambda Fellow, 2011 Hedgebrook Fellow, and 2012 Squaw Valley Fellow, Meg completed her MFA at Mills College and publishes the femme ally zine ON OUR KNEES out of Salt Lake City. A 2012 AWP Intro Award Winner, Meg’s most recent work can be found in or is forthcoming from Rattle, Southern Humanities Review, Fugue, Troubling the Line: An Anthology of Trans and Genderqueer Poetry & Poetics, Flicker and Spark: An International Queer Poetry Anthology, This Assignment is So Gay: Poems from LGBTQ Teachers, The Atlas Review, and in the chapbook

When All You Have is a Hammer, planned for publication in 2013 by Gertrude Press. Her website is

MEG DAY is a 2013 recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Poetry, three-time Pushcart-nominated poet, nationally awarded spoken word artist, and veteran arts educator who is currently a PhD fellow in poetry and disability poetics at the University of Utah. Meg hails from Oakland, where she taught young poets to hold their own at the mic with YouthSpeaks and as a WritersCorps Teaching Artist in San Francisco. A 2010 Lambda Fellow, 2011 Hedgebrook Fellow, and 2012 Squaw Valley Fellow, Meg completed her MFA at Mills College and publishes the femme ally zine ON OUR KNEES out of Salt Lake City. A 2012 AWP Intro Award Winner, Meg’s most recent work can be found in or is forthcoming from Rattle, Southern Humanities Review, Fugue, Troubling the Line: An Anthology of Trans and Genderqueer Poetry & Poetics, Flicker and Spark: An International Queer Poetry Anthology, This Assignment is So Gay: Poems from LGBTQ Teachers, The Atlas Review, and in the chapbook

When All You Have is a Hammer, planned for publication in 2013 by Gertrude Press. Her website is